Mayer’s 12 Principles of Multimedia Learning, Part 1: Reducing Extraneous Load:

The 12 principles of multimedia learning were developed by Richard E. Mayer. They are designed to optimize learning by taking advantage of insights from cognitive science.

The goal of these multimedia principles is to cut down on unnecessary mental effort, manage the difficulty of the content, and improve the way learners process information. They use both visual and auditory channels to maximize learning, ensuring that educational content is presented in the most effective way possible.

Practical Limitations

These guidelines help to maximize learning and are helpful when deciding how to design and build your training.

In an ideal world, you would apply all these principles in each and every training you design. However, in the real world, there are limitations to what you can do.

When designing your training, you’ll also have to consider, among other things:

Technological constraints

Deadlines

Budget

Scalability

User accessibility

Organizational politics

While working within these limitations may make it more difficult to implement each of the principles, they provide a realistic framework.

Value Analysis

In addition to understanding your limitations, you will also need to consider the value that is added by following these principles. While each of these principles enhances learning to some degree, some principles may be more difficult to follow.

For example, placing labels close to the objects they are labelling (spatial continuity principle) is easier than hiring voice actors to provide narration (voice principle). The second is much more expensive and time-consuming.

Consider the cost of following these principles. If including a particular element would double the cost to develop the training, it may not be worth the incremental benefit in learning.

Reducing the Extraneous Load

The brain has as limited ability to process information, so you don’t want to waste any of the learner’s cognitive effort on unnecessary information.

Each bit of extraneous information detracts from the learner's ability to focus on and retain essential concepts.

Effective teaching minimizes cognitive load by presenting information clearly and concisely to avoid wasting any of the learner’s brain power on unnecessary input.

Designing learning experiences with this principle in mind ensures that learners can use their mental energy to understand and integrate new knowledge. Prioritizing relevant content enhances comprehension and retention rates, optimizing the learning experience.

In short, eliminating unnecessary information fosters better learning.

There are a few principles to keep in mind to help you reduce the extraneous load for your learner.

1) The Coherence Principle

The coherence principle states that all materials that are presented to the learner should be essential and support the learning objectives.

Learning a new concept can tax the cognitive abilities of the brain, so it’s important not to include any information or stimulus that does not support learning. The conscious mind can only hold 5-9 pieces of information at a time. When you present the learner with unnecessary information, it distracts them from what’s important.

Even so, including “extra” information can be tempting.

This would be nice for the learner to know, you think. But these pieces of nice-to-know information takes effort to process – effort that could be used to process the important information.

To put it another way, “Why use two words when one will do?”

Similarly, visuals should be relevant to the learning objectives and only include as much detail as necessary to illustrate a concept.

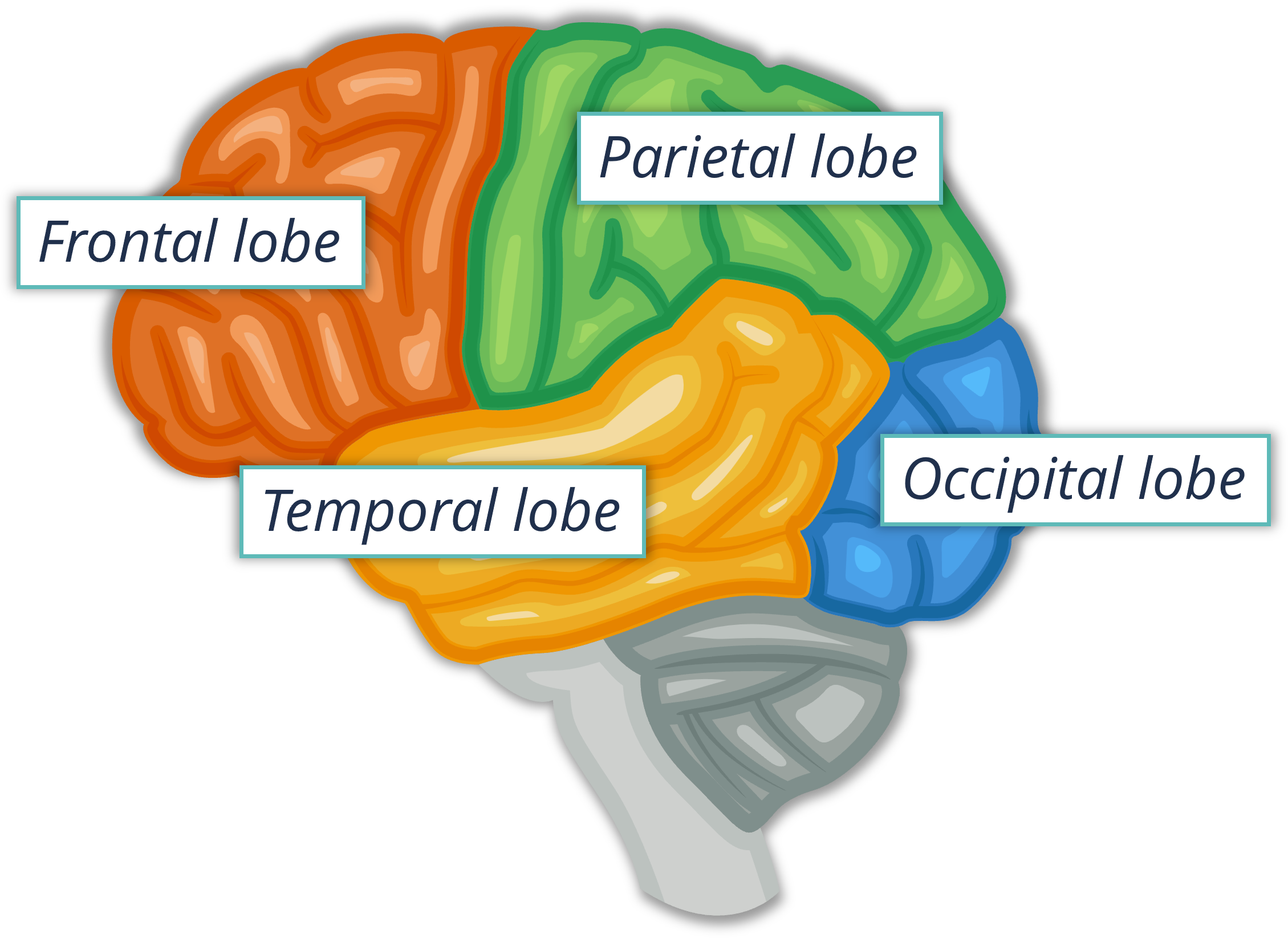

Consider the two images below.

The extra details in the graphic of the man does not support the learner’s understanding of the brain.

Graphic of a man with an image of a brain with the four lobe areas labeled.

The second image allows the learner to concentrate on the important information.

Graphic of a brain with the four lobe areas labeled.

A decorative graphic or “Did You Know?” piece of trivia might seem to make training more interesting, but all it does is take up space in the working memory – space that could have been used for learning.

In a similar vein, using animated videos, rather than recording real humans, can reduce the cognitive load of the learner. Animated videos, like those produced in Vyond, have fewer details and less information for the learner to process.

Background music and sound effects may also be unhelpful and do not usually support the learning objectives. Music, even without lyrics, can distract the learner from paying attention to other information, such as what the narrator is saying.

Additionally, these distracting pieces of information can make it more difficult for the learner to organize the new information into a schema (or framework) in long-term memory as they sift through which information is actually important.

As you preview your learning materials, ask yourself, “How can I shorten this text while still maintaining the essential information and meeting the learning objectives?” or “Is there anything I can remove from this slide?”

You may need to ask similar questions when interviewing a SME to make sure they are not asking you to include information that does not support the goal of the training you are designing.

Ask Yourself

Do all the materials (visual and auditory) support the learning objectives?

What unnecessary information can I remove?

2) The Signaling Principle

The signaling principle states that all essential information should be pointed out to the learner.

If we follow the coherence principle, all the information we include in a training should be important. However, signaling to the learner which information is most important to understand, or pointing out key terms, can help the learner focus their attention more effectively.

Additionally, drawing attention to key terms or main ideas can help the learner organize the information and structure it into a framework. In this way, highlighting key terms can work similarly to using titles and headings to organize information.

Signaling can also help the learner with retention, as highlighting key information can make that information more distinct, and therefore more memorable.

Finally, highlighting key information can make it easier for the learner to review the content. Even if the learner is looking for information that was not highlighted, they may be able to find it more easily because they remember the key term or idea that was related to. This reduces the cognitive effort it takes to review information.

There are several different ways to point out key information:

Use bold, italicized, highlighted, or underlined font to draw attention to key text.

Use arrows, circles, boxes, or color can draw attention to important objects in visuals.

Provide a pop-up caption to highlight a key term in a narration.

Ask Yourself

Is key information highlighted?

Is the learner guided to focus on important information?

3) The Redundancy Principle

The redundancy principle states that visuals should be explained through narration or text, but not both. However, if you refer to the modality principle, you can see that narration is the preferred method to explain graphics.

As an example, think back to a time you watched a movie or YouTube video with subtitles on. Did you miss something that was happening on-screen because you were reading the subtitles instead?

The redundancy principle suggests that providing on-screen text that mirrors voiceover (like subtitles for a video) can distract the learner from the on-screen visuals, rather than reinforce learning. However, if the learner is hard of hearing or has limited language abilities, they may need captions to understand the content.

An exception to this is for key terms or short summary statements that support, but do not replicate the narration.

For example, the voiceover for an animation may state, “Information in long-term memory is organized into ‘schemas’ or frameworks that organize information by putting it into categories and relating concepts to each other.”

While including the entire statement in the subtitles violates the redundancy principle, the key term “schemas” is an important term, and it may be helpful to include this word as on-screen text to help support learning.

Additionally, you may include a short summary statement. For example, you might include on-screen text that states, “schema = information framework” to reinforce the narration’s key idea.

Voiceover script describing a graphic that represents a schema related to instructional design.

This concept relates back to the signaling principle already discussed.

Following the redundancy principle reduces cognitive load by distributing the information between the visual and auditory channels instead of overloading the visual channel through repetitive images and on-screen text.

If you provide closed captions to make your training accessible, do not make this option the default. This will discourage users who do not need subtitles from distracting themselves through this feature.

Ask Yourself

Are visuals explained through narration or text, but not both?

4) The Spatial Contiguity Principle

The spatial contiguity principle states that graphics and corresponding text should be displayed in close proximity to each other.

Think about the effort it takes to look back and forth between a graphic and a list of items. In the image below, the learner must look at the list of regions in the brain, find the corresponding marker to see where that item is located on the brain, and then move on through the list.

An image of a brain with numbered markers next to a numbered list of what each marker shows.

Now consider the image below. The cognitive load required to decipher this labeled graphic is much lower. The learner does not need to divide their attention between a list and the corresponding markers. Instead, the labels are in the right spot.

An image of a brain with 4 regions color-coded and labeled with the name of that lobe.

In some cases, there may not be enough room to display text near the corresponding graphic. If the learner does not need to view all the information at once, a label that pops up when the learner hovers over the area may be appropriate.

Additionally, directions should always be visible while the learner is following them. Place them as close to the learner input area as possible, without becoming distracting, so that the learner can reference them as needed.

Similarly, answer feedback should be displayed next to the learner’s submission so that the learner can compare their answer with the correct one.

Requiring the learner to switch between slides or tabs or remember directions from a previous slide imposes unnecessary cognitive load, making learning more difficult.

Ask Yourself

Are graphics and corresponding text shown close together?

Are directions visible while the learner follows them?

Is feedback shown next to the learner’s response?

5) The Temporal Contiguity Principle

The temporal contiguity principle states that related audio and visual information should be presented at the same time. This concept is very similar to the spatial contiguity principle we just discussed.

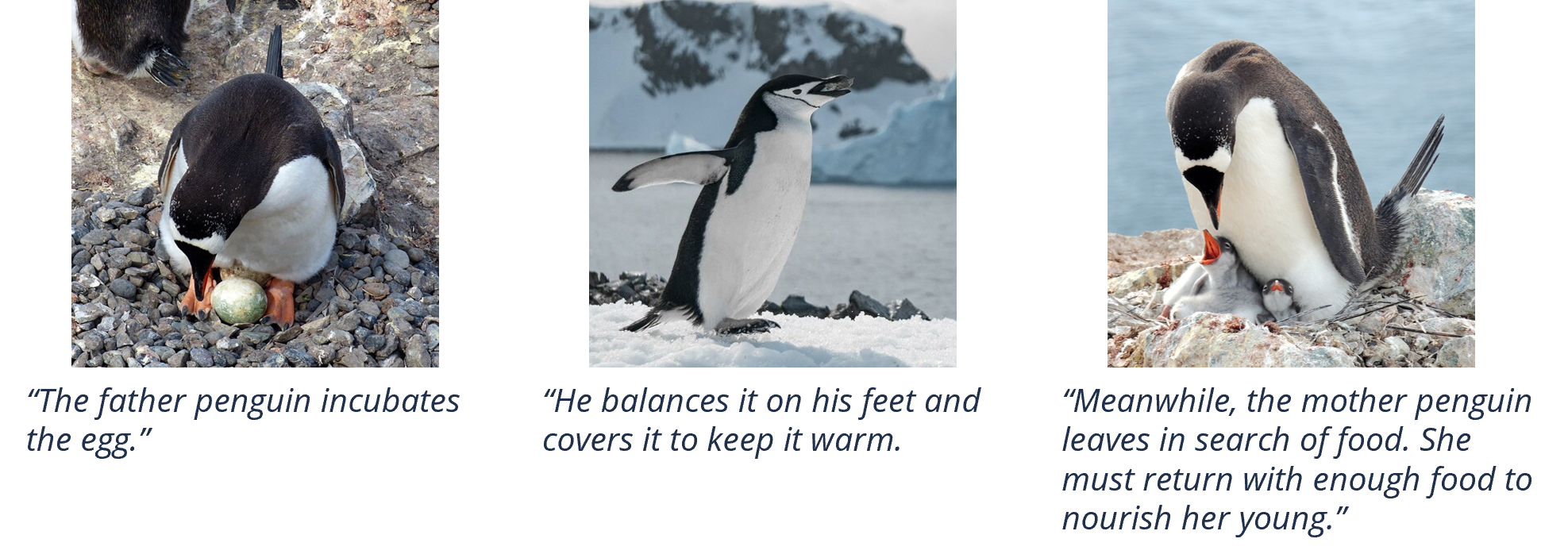

Consider a fictitious Planet Earth documentary about penguins. Perhaps the narration says, “The father penguin incubates the egg, balancing it on his feet and covering it to keep it warm. Meanwhile, the mother penguin leaves in search of food. She must return with enough food to nourish her young.”

The timing of the narration in relationship to the video is important. Consider the timing shown below.

Three images of penguins with narration script that is not synced correctly.

Did any of that confuse you?

Why is a lone penguin shown as the narration continues to talk about how the father keeps the egg warm? you may ask.

In some videos, the narration may lag behind the visuals (or vice versa). If this happens, the learner can become confused as they try to find a connection between spoken words and images that are unrelated. To make sense of the information, they must hold the visuals in working memory until the narration catches up, wasting cognitive effort on something that could have been avoided.

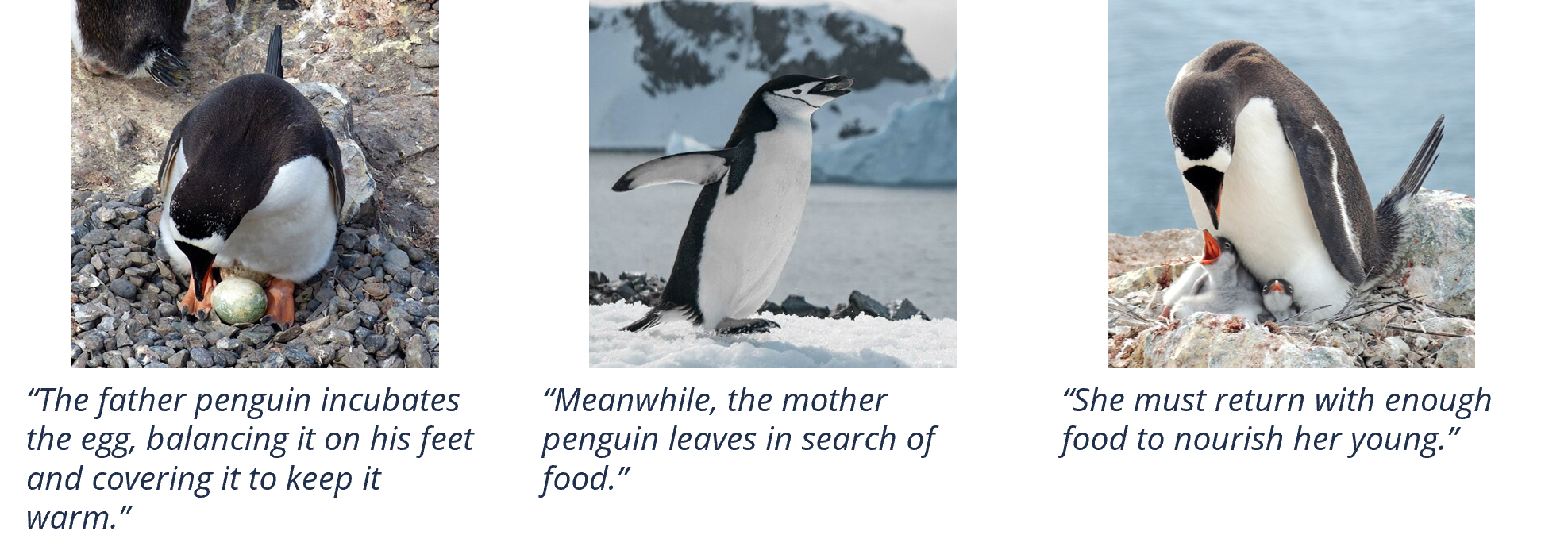

Presenting the related information at the same time makes it easier for the learner to make connections between the audio and visual information. Consider this example:

Three images of penguins with narration that is synced correctly.

Here, the narration is played at the same time as the corresponding images. The learner can process the related information at the same time, using both the auditory and visual channels to distribute the cognitive load.

Ask Yourself

Is related audio and visual information presented at the same time?

Is narration synced accurately?

A Note on Gamification

While Mayer did not directly address gamification through any of his twelve principles, it is worth noting the benefits and drawbacks of this approach.

Gamification has become very popular in recent years. It can increase engagement and help motivate the learner to continue through the course. It can also provide timely feedback to the learner about their answer choices.

However, gamified learning experiences can require cognitive effort to navigate. The more complicated the gaming elements are, the more effort it takes to play the game.

As we know, learners have a limited capacity to process information. If they use their cognitive energy to figure out how to navigate the game, their capacity to learn the lesson content may decrease.

If our goal is to reduce the extraneous cognitive load of our learners, we need to be careful with the gamification elements we choose to include in our courses.

Consider the difference between an escape room style training like the one shown below compared to a training that gives the learner coins for each answer they get right.

Two examples of gamification. On the left is an escape room. On the right are two coins.

When completing the escape the room training, much of the learner’s energy is used to figure out the clues rather than learn the content. However, receiving coins for correct answers is engaging, motivates the learner, and does not distract from learning.

Ask Yourself

Is this gamification strategy more motivating or distracting?

Are there any aspects of the gamification that I can simplify?

Conclusion

Incorporating Mayer's principles of multimedia learning into instructional design is not merely about following guidelines; it's about optimizing the learning experience by reducing unnecessary cognitive load.

By prioritizing principles such as coherence, signaling, redundancy, spatial contiguity, and temporal contiguity, you can streamline content delivery to enhance understanding and retention.

Understanding the practical limitations and evaluating the added value of each principle allows for strategic decision-making in course development.

Ultimately, by minimizing extraneous information and distractions, we empower learners to focus their cognitive resources on assimilating and applying essential knowledge effectively.